The 1919 massacre at Amritsar – known more prominently in history as Jallianwala Bagh Massacre – is easily one of the most sordid episodes of the chequered history of India. As history goes, the inhuman chain of events on the fateful day was spawned by General Reginald Dyer. The incident took place on 13th April – a Sunday when the whole of Punjab was celebrating Baisakhi.

Baisakhi is the festival that heralds the beginning of Khalsa Panth in 1699 by Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Guru of Sikhs. Yet, on this particular occasion, life came to a complete standstill – not only in Punjab but across the country – thanks to the repressive thought process and consequent actions of a British officer with nothing but subjugation in his mind.

The impact that the genocide created can be gauged from the fact it moved Rabindranath Tagore to such an extent that he refused the colonial masters’ proposal to be knighted. It was even criticized by Winston Churchill.

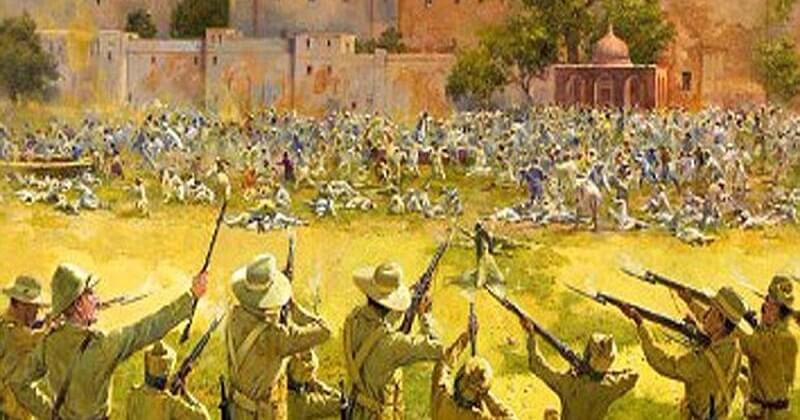

On that day, under the stewardship of General Dyer, 90 soldiers of the British Indian army came to a gathering being organized at Jallianwala Bagh. Of them, 25 were from Baluchistan, which is now a part of Pakistan, and the rest were Gorkha soldiers. These 90 soldiers were armed with guns.

Dyer had also brought a couple of armoured cars with mounted machine guns, but since the entrance to the ground was narrow, he had to leave those cars outside. Dyer had himself stated later on that if he had taken those cars inside the gates the casualties could have been higher. The meeting had started at 4:30 pm – the scheduled time – and Dyer reached the place an hour after that.

Dyer first marched his riflemen to a raised platform and from there he ordered them to kneel and fire. Having got there, they started to shoot on the people who had gathered there. Apart from men, the gathering included women and children. They did not even bother to warn the people who had assembled over there.

It is known that there were so many people at the Bagh that the soldiers had to reload a number of times as they were ordered to shoot with the precise intention to kill. It is said that they fired 1,650 rounds in all! When one considers that the assembly of people at the Bagh was unarmed, the sheer monstrosity and general apathy towards human life reflected in the genocide strikes one’s consciousness.

At the end of the killing spree, 379 individuals had lost their lives according to estimates by British Raj. Over a thousand persons were wounded to various extents. According to Dr. William DeeMeddy, a civil surgeon at that time, 1,526 people had either died or been injured. Indian National Congress estimates had placed the number of casualties at 1,500 with around 1,100 people losing their lives.

The Bagh was blocked on every side by buildings and houses. There were some narrow entrances but most of them had been locked permanently. The main entry had already been blocked by the shooters. Dyer had not given these people any warning that he was going to shoot them and as such they were not prepared to escape or even plead for mercy.

He had also asked his soldiers to shoot at the densest parts of the gathering. Shooting was, however, not the only cause for these deaths. Many people lost their lives in the ensuing stampede as well. A lot of people tried jumping into the well located in the garden. The plaque at that site says 120 dead bodies had been recovered from the well. The colonial government was also thoughtful enough to have declared a curfew on that night, which ensured that a lot of the wounded people could not be moved on that day. This led to more deaths.

Aftermath

The colonial administration instituted an inquiry committee to look into the genocide in July 1919 – three months after the incident – and invited people to come forward and report any death or injury that may have occurred during that fateful day. It was on basis of that faulty method that it reached its calculations. One can assume here – and rightfully so – that not many people would have been too willing to come forward and thus be marked by the British Raj. In fact, some members admitted that the figure may have been higher than the official statistic.

As is usual in such circumstances, the British government tried its best to make sure that news of the killings did not spread all around. However, it did come to national notice and there was furious backlash. People in Britain got to know of this only by December 1919.

In his communication with his superiors, Dyer termed the unarmed congregation that he slaughtered to be ‘a revolutionary army’. His actions were officially approved by O’Dwyer. He had asked for martial law to be imposed on Amritsar and it was granted by Lord Chelmsford, the-then Viceroy, following the massacre.

Edwin Montagu, then the Secretary of State for India, led Hunter Commission, which was created in later 1919 to look into the incident. Dyer appeared before the commission, but he showed no compunction for what he had done. Since his superiors had supported his actions, the commission did not sentence any disciplinary or punitive measures. He was later, however, found guilty of a mistaken perception of duty and excused from his post.

O’Dwyer was later killed at Caxton Hall, London on 31st July, 1940 by Udham Singh, who had watched the whole event with his own eyes as an orphan.

Post Your Comments