The skull of one of the first limbed creatures has been digitally reconstructed by researchers from the University of Bristol and University College London using cutting-edge technology.

Mammalian, reptile and amphibian tetrapods encompass everything from salamanders to humans. Their emergence marks a pivotal point in animal evolution, beginning with the development of digitised limbs and the transition from water to land.

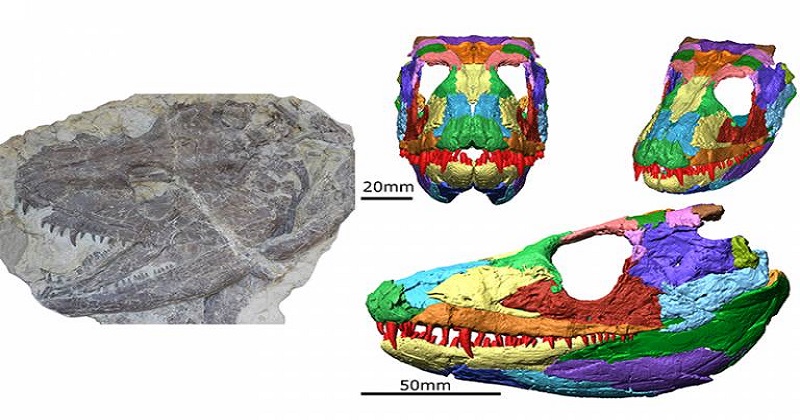

The rebuilt skull of an ancient amphibian, the 340-million-year-old Whatcheeria deltae, is depicted in the study, which was recently published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, to explain what this animal looked like and how it may have been nourished.

The fossils of Whatcheeria were discovered in Iowa in 1995 and were initially crushed flat after being buried by muck at the bottom of an old marsh, but palaeontologists were able to reconstruct the bones to their natural configuration using computer methods.

A CT scanner was utilised to generate accurate digital reproductions of the fossils and software was employed to isolate each bone from the surrounding rock. These digital bones were then mended and reconstructed to create a 3D model of the skull as it would have appeared if the animal had been alive at the time.

Whatcheeria had a tall and thin head, unlike many other early tetrapods alive at the period, according to the researchers. Lead author James Rawson, who worked on the research while studying palaeontology and evolution as a student, said: ‘Most early tetrapods had very flat heads which might hint that Whatcheeria was feeding in a slightly different way to its relatives, so we decided to look at the way the skull bones were connected to investigate further.’

The investigators were able to figure out how this animal attacked its victim by following the sutures that link the skull bones. Professor Emily Rayfield of the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol, who was also involved in the research, said: ‘We found that the skull of Whatcheeria would have made it well-adapted to delivering powerful bites using its large fangs.’

Also Read: Researchers convert water into shiny golden metal

Co-author Dr. Laura Porro said: ‘There are a few types of sutures that connect skull bones together and they all respond differently to various types of force. Some are better at dealing with compression, some can handle more tension, twisting and so on. By mapping these suture types across the skull, we can predict what forces were acting on it and what type of feeding may have caused those forces.’

The nose had a lot of overlapping sutures to resist twisting pressures from fighting prey, but the back of the skull was more securely linked to prevent compression while biting, according to the researchers.

Rawson added: ‘Although this animal was still probably doing most of its hunting in the water, a bit like a modern crocodilian, we’re starting to see the sorts of adaptations that enabled later tetrapods to feed more efficiently on land.’

Post Your Comments