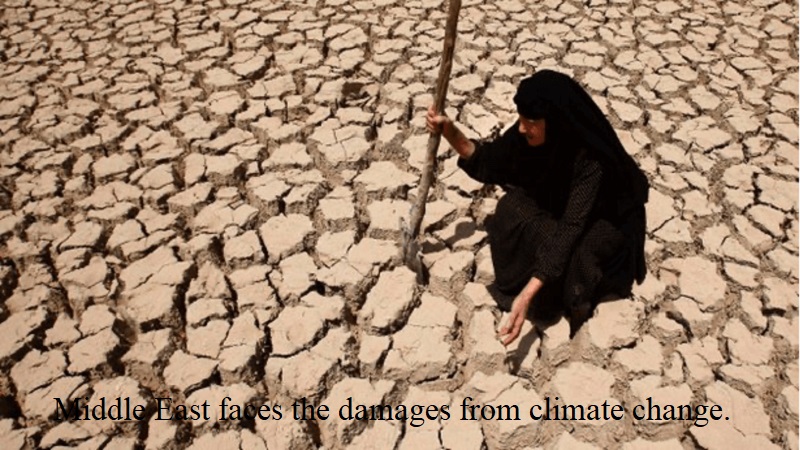

In the past three decades, temperatures in the Middle East have increased far more quickly than the global average. Since precipitation has been falling, experts believe that droughts will become more frequent and severe.

One of the areas in the world that is most susceptible to the consequences of climate change is the Middle East, and those effects are already being felt.

This year, severe sandstorms in Iraq have regularly engulfed towns, halting business and bringing thousands of people to hospitals. Important agriculture in Egypt’s Nile Delta is being destroyed by rising soil salinity. Drought in Afghanistan has encouraged young people to leave their homes in search of employment. Some areas of the region have experienced temperatures above 50 degrees Celsius in recent weeks (122 Fahrenheit).

The annual COP27 summit of the United Nations on climate change is taking place in Egypt in November, drawing attention to the area. Middle Eastern governments are now aware of the risks posed by climate change, notably the harm it is already doing to their economies.

“We are practically witnessing the results right before our eyes. These effects won’t be felt by us in nine or ten years, according to Lama El Hatow, an expert on the Middle East and North Africa and a climate change consultant who has worked with the World Bank.

She claimed that more and more states were beginning to see the importance of taking action.

Egypt, Morocco and other countries in the region have been stepping up initiatives for clean energy. But a top priority for them at COP-27 is to push for more international funding to help them deal with the dangers they are already facing from climate change.

One factor making the Middle East vulnerable is that there is just not enough room to absorb the impact on millions of people as global temperatures rise faster than expected. Even under normal conditions, the region already experiences high temperatures and scarce water supplies.

The International Monetary Fund observed in a report earlier this year that governments in the Middle East also have a limited capacity to adapt. Regulations are frequently ignored, and infrastructure and economies are inadequate. Because poverty is so pervasive, creating jobs takes precedence over protecting the environment. Civil society is heavily restricted by autocratic governments like Egypt’s, which makes it difficult to use a crucial instrument for educating the public about environmental and climate challenges.

At the same time, developing nations are pressuring countries in the Mideast and elsewhere to make emissions cuts, even as they themselves backslide on promises.

The threats are dire.

The United Nations has warned that the Mideast’s food production may decline by 30% by 2025 as the region becomes hotter and drier. The World Bank estimates that the region will lose 6 to 14 percent of its GDP due to water scarcity by 2050.

According to the World Bank, precipitation has decreased 22 percent in Egypt during the previous 30 years.

The frequency and severity of droughts are predicted to increase. According to NASA, the Eastern Mediterranean recently saw its worst drought in 900 years, which was devastating for nations like Syria and Lebanon whose agriculture depends on rainfall. The demand for water in Jordan and the nations of the Persian Gulf is unreasonably straining aquifers. In Iraq, the increased aridity has caused an increase in sandstorms.

At the same time, catastrophic and frequently damaging weather events—like the deadly floods that frequently lash Sudan and Afghanistan—become more frequent due to warming waters and air. The effects of the climate damage on society could be very dangerous.

According to Karim Elgendy, an associate fellow at Chatham House, many people who lose the livelihoods they once had in agriculture or tourism would relocate to the city in search of employment. According to Elgendy, who is also a non-resident scholar with the Middle East Institute, this will probably lead to an increase in urban unemployment, a pressure on social services, a rise in social tensions, and a threat to national security.

For this year’s COP, the top theme repeated by U.N. officials, the Egyptian hosts and climate activists is the implementation of commitments. The gathering aims to push countries to spell out how they will reach promised emission reduction targets — and to come up with even deeper cuts, since experts say the targets as they are now will still lead to disastrous levels of warming.

Developing nations will also want wealthier nations to demonstrate how they will follow through on a pledge made at the previous COP to contribute $500 billion in climate financing over the following five years, with at least half of that money going toward adaptation rather than mitigation.

The impetus from COP26, however, is in danger of being undermined by global events. Regarding carbon reductions, the rise in energy prices globally and the conflict in Ukraine have led some European nations to resume using coal for electricity generation, though they say this is only a temporary measure. A number of Middle Eastern nations, most notably Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf, but also Egypt with its rising natural gas production, rely on their fossil fuel resources for their economies.

Persistent inflation and the possibility of recession could make top nations hesitant on making climate financing commitments.

El Hatow said it is important to remember that although international politicians frequently emphasise emission reduction, the majority of the effects of climate change are being felt in developing nations like those in Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere in the world.

She remarked, ‘We need to talk about finance for adaptation to deal with a situation they did not create.’

The IMF predicts that it will cost the region the equivalent of 3.3 percent of its GDP annually for the next 10 years to adapt infrastructure and economies to the damage. The funds must be used for anything from developing new farming practises and more effective water use systems to protecting coastlines, strengthening social safety nets, and enhancing public awareness campaigns.

So one of top priorities for Mideast and other developing nations at this year’s COP is to press the United States, Europe and other wealthier nations to follow through on long-time promises to provide them with billions in climate financing.

So far, developed nations have fallen short on those promises. Also, most of the money they have provided has gone to helping poorer countries pay for reducing greenhouse gas emissions — for ‘mitigation,’ in U.N. terminology, as opposed to ‘adaptation.’

Post Your Comments